Hindi Mahotsav: Hindi Criticism: A New Reading

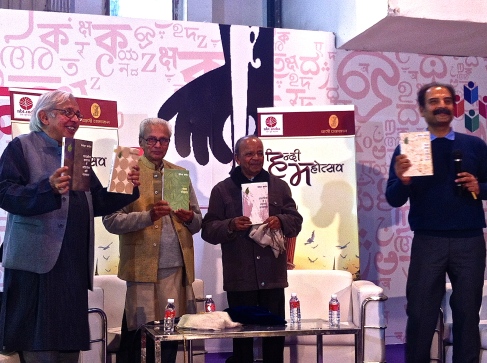

On February 21st cultural and literary critics Ashok Vajpayee and Manager Pandey contributed to the democracy of ideas at the Delhi World Book Fair when they attended Vani Prakashan’s event, “Hindi Criticism: A New Reading.” The two critics practice different schools of literary theory, but demonstrated their shared commitment toward the relevance of literature to society. The relevance of literature to democracy was given ample opportunity to prove itself at the Hindi Mahotsav when two Hindu fundamentalists, infuriated by a comment on the panel, hijacked the discussion and instigated religious-inspired pandemonium.

The relationship between literary criticism and society might not be immediately apparent to everyone. “What do aesthetics have to do with economic policies, political rallies, and diplomatic relations after all,” one might ask? The answer is: a lot. Literary critics perform the necessary social responsibility of selecting from an uncountable number of scholarly and literary texts the most philosophically thought-provoking, stylistically crafted, or socio-politically salient works. The careers of Vajpayee and Pandey evince this responsibility—a duty they performed again by defending free dialogue at the Lekhak Manch this past Thursday.

Ashok Vajpayee is a Hindi poet, critic, essayist, and administrator of several cultural and arts institutions. According to The Kavita Trust Foundation, he has written, “13 books of poetry, 10 books on criticism, 4 books on art in English.” He is described as “a frequent presence at some of the major literary conferences, seminars, and poetry festivals,” where, “he has raised his voice for the autonomy of literature and the arts, as against contemporary tyrannies of ideologies, markets, and fundamentalism.” He has received prestigious awards, including the Sahitya Akademi Award, Dayawati Kavi Shekkhar Samman, and Kabir Samman.

Manager Pandey is a Hindi professor at the Indian Language Center of the Language Institute at Jawaharlal Nehru University. Pandey was the focus of the panel. His five new books released by Vani Prakashan reflect the wide variety of his intellectual engagements: Aalochna Mein Sehemiti Aur Asehemiti (Agreement and Disagreement in Criticism), Upanyas Aur Loktantra (The Novel and Democracy), Bhartiya Samaaj Mein Pratirood ki Parampara (The Tradition of Resistance in Indian Society), Samvad Parisamvad (Dialogue and Discourse) and Hindi Kavita Ka Atit Aur Vartman (The History and Present of Hindi poetry). The recipient of the Sahitya Akademi Delhi Author’s Award and Rashtriya Dinkar Samaan, he has been praised for his groundbreaking commentary on debates on the newly emergent Dalit and Feminist literature movements.

Vajpayee praised Pandey for his academic thoroughness. It was an extremely important element of criticism, he remarked, which has been missing from Hindi for some time. Vajpayee went on to say that Pandey’s most distinctive attribute as a critic is his intellectual range–his ability to join divergent aspects of the world together and bring constantly into focus the context of Indian society.

“It is not as if you love poetry you don’t love Marxism, or love Marxism you don’t love poetry,” Pandey explained, referring to the theoretical differences he and Vajpayee shared with regards to aesthetics. His flattery from Vajpayee’s adulations was evident by his smile.

The conversation shifted to the definition of Marxism in the twenty-first century. The topic of Marxism brought with it a separate discussion on the necessity of co-existence between contending opinions in society and literature. Ashok recounted great Hindi writers and critics in the past—Premchand, Nirala, and Muktibodh—whose works had become “Vyarth” (irrelevant) with the passage of time.

Vajpayee also commented on the way Marxist ideology was in new way uniform: critics like Pandey inject new life into Marxist thought through their creative reinterpretation and engagement. “Where we stand at the present time, literature and society are the same,” Vajpayee said. “And so long as democracy lives, the relationship between the novel and democracy will continue.” Adding to this thought, Pandey said the way forward for contemporary development won’t emerge from a single mind , but the consciousness of an entire movement.

It was also a particular brand of contemporary Indian consciousness (often linked with development) which sparked a violent disruption of the panel. Ironically, the disruption did not occur as the result of Marxist opposition, but rather offense taken at an aside concerning religion. Pandey commented that Tulsiram—a famous Hindu Bhakti saint—”Could also be considered a literary critic.” Pandey’s perspective ignited criticism from two Hindus in the audience, who began waving, gesticulating, and shouting angrily at the panelists.

This virulent religious outcry threw the audience into utter pandemonium. In the shouting mayhem that ensued, it was not quite clear what had been said to cause the offense. A student sitting next to me, noticing my confusion, turned to whisper in my ear, “Religion is like a drug here.” Other Indians seated nearby glanced at me to ascertain what the only American in the crowd could be thinking.

The moderator, meanwhile, struggled to maintain order. “Tulsiram can be a critic!” he roared, infuriated by the instigator’s lack of respect for the panelists. Pandey–seeking to douse a fire that was only growing larger by an excited audience and fascinated passerbyes– seized the microphone and stepped to the front of the stage.

“I was only trying to say that the job of literature is to make a person human and democratic,” he said emphatically into the microphone. “If someone thinks differently than you, if someone experiences differently than you, then honoring that difference is democratic!”

Pandey’s entreaty was met with a round of applause. An “Us” versus “Them’ mentality was formed as half of the audience returned to their seats while the other half continued shouting with Tulsiram’s defendants in the hallway. The panel discussion continued, but their time was mostly over.

At the end of the event I passed by the warring crowd, curious about what they were saying. One man shouted—“So this is your beautiful culture!”—referring to Hindu nationalism. Later, in a nearby bookstore, several audience members shook their heads and spoke lowly amongst themselves. “We are all Hindus too,” one woman said, embarrassed by what had transpired. “But we do not all act this way.”

Once again, it was not clear what had led to the men’s explosion in the audience. But whether they interrupted to gain attention as a political ploy, or whether they were driven to the edge of civility because of a religiously inspired madness, the manner in which they hijacked the conversation and remained deaf to entreaties to politely field their questions served to only reify the discussions’ main topic:

Respecting divergent opinions in literature and democracy.

Far too often, it seems, both within India and the United States, civil public discourse is sidelined by extremist fringe groups. What occurred that day is only one instance of a much more widespread political problem —a problem further aggravated when individuals (whether they be audience members or media personnel) give attention to straw men, rather than letting hallow voices show themselves out silence.

I find it reassuring that while this tamasha sparked and died over the course of an hour, a more serious, thought provoking dialogue continues to unfold in the form of books between readers and writers. In any good democracy, opinions should be expressed and opinions should be heard.

Literature waits for it’s opportunity to speak, and we—as citizens and readers—have the power of the critic to choose and to listen.